Project: ALICE was always going to be very ambitious, particularly from a technical perspective. For me it felt like I was doing one of those rare projects where we could go all out on the technical production. There was no such thing as 'too much' (as long as we could afford it). Often we were consciously trying to induce a trance-like response in the audience. It was a big risk, but it paid off with a show that looked absolutely amazing.

The lighting was a co-design between myself and the director, Mark Haslam. I've know Mark for about six years and this was the first time we've done a show together. Unlike many directors Mark has a strong background in technical theatre, as well as an impressive literary and physical practice. It's one of those odd things that in Australian theatre director training is based on working with actors and text and so they often rely on designers to supply nearly all of the technical direction. Which is the opposite of many Australian film and TV directors whose training is primarily based around cameras and technology. In both cases I think a balanced approach gets the best results, which is why it was particularly good to work with Mark.

Alice in Wonderland

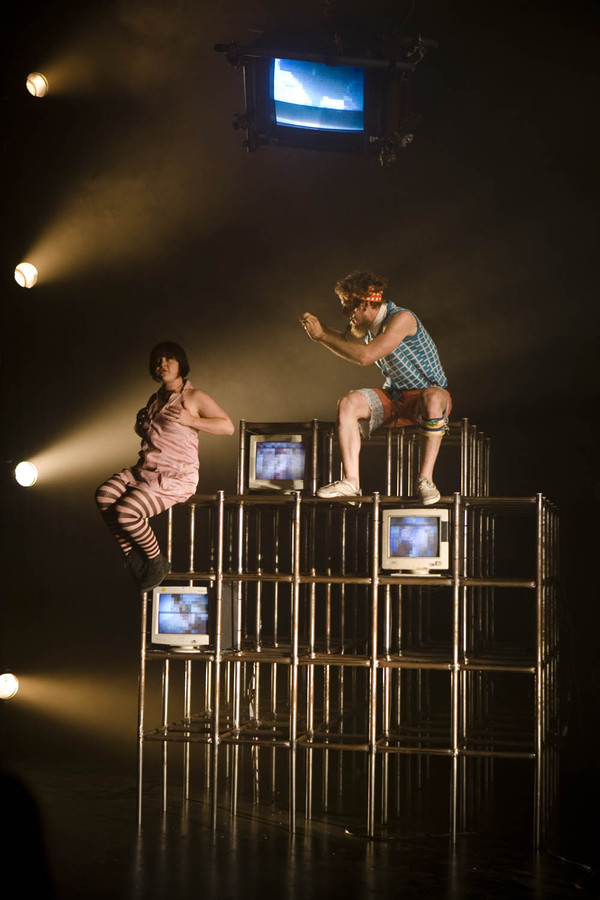

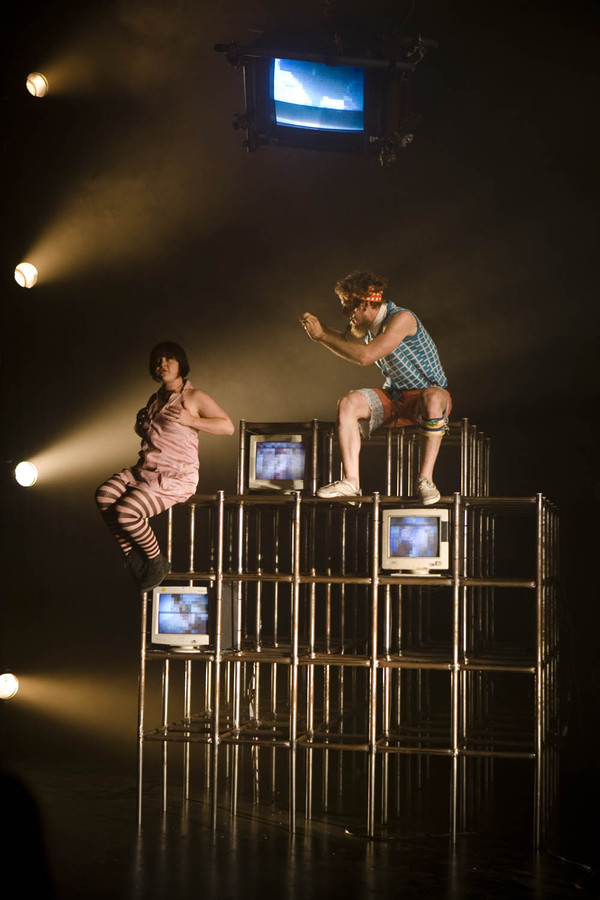

Alice in Wonderland is the story of a young person lost in a senseless world. For this production we placed Alice in a generation Y context, mixing real stories from our Gen Y writers with Lewis Carroll imagery. Our main setpiece was a rusted jungle gym, infested with televisions and computer monitors. For the lighting Mark came to me with a concept of several tall booms surrounding the space rigged with open white par-cans. The idea was to provide a stadium-esque sense of depth, so that the production could move from intimate moments to huge over-the-top rock and roll looks. Chases and movement allowed a sense of playfulness in contrast to the threat of being completely overwhelmed by the intensity of the light. We specifically referenced images of night clubs, city lights and the blinking of neon advertising.

In practice the par cans proved to be an amazing depth effect. With so many pointing directly in the audiences eyes we had to be very careful not to blind, rarely taking them above 15%. I found that when they were just glowing, at about 5%, your eyes would adjust so that all you could see behind them was pure darkness - much better than seeing a bunch of black drapes at the back of the space.

We wanted each par 64 to be individually controlled. I also wanted to run our lighting desk in two preset mode. This meant that I was limited to 48 DMX control channels in total and of these 48 channels we needed to use 32 for our parcans, plus another 7 for our hazer and strobe. This left only 9 channels for lights that weren't open white par-cans pointing straight into the audience. For me this was a big risk - I was 'investing' three quarters of my potential control into a bunch of lights that might only provide two or three different looks. For a production that wanted to go so many different places it seemed insane to have so little variety. There was no way I was going to have enough channels left to do anything else and have a proper front-of-house rig so in the end I took another risk and cut FOH lighting completely. This meant there would be no conventional face light from the front - faces would be lit entirely from the sides.

I can say now that those risks were all worth taking. I found that the parcans were incredibly flexible. They created their own brand of 'parcan architecture' - even simple patterns were entrancing. The reason I use the word architecture is that their various arrangements seemed to suggest a sort of logic or coherence in their relationship to one another. This made them seem like a much more natural setting for the action than a bunch of lights on stands might otherwise seem. Track 8 is unusual as a small venue in that it has a fairly high ceiling. My top parcans were at 5.2m in the air, giving a sense of something ascending into the darkness. A chase from the top to the bottom of a boom would give the feeling of light falling from above. The stands were arranged so the cans filled your peripheral vision. Various chases at a low intensity were reminiscent of the flickering patterns you see when you close your eyes tight. In this way you could suggest both the huge depth of a stadium and the intimacy of something you only experience behind your own eyelids - simultaneously.

Occasionally I see shows that use a great deal of atmospheric effects and I think they draw attention to the lighting at the expense of the action, but for this particular show I can't understate how much value the use of haze actually brought to the production. The great thing about using haze with tungsten lights is that it brings the life of the filament out onto the stage. Suddenly the audience can see the light ramping up, heating up, as it excites the air in front of it - seemingly moments before it is seen onstage. I think it worked for ALICE because this life was actually taken into account in the lighting design. All the fades were designed to draw the eye to the lamp first and then follow the beam to it's target. The haze meant that there was truly a difference between 5% and 10%, from a glowing eye to a column of light. Haze was provided by a

Look Solutions Unique 2, which did the job beautifully.

We had one more trick up our sleeves in the lighting department: a

Martin Atomic 3000 Strobe, which was kindly lent to us by a friend. However as we had no colour in the rig we decided to fit a colour scroller to it, so that on top of our tungsten warmth we could cut to some saturated primary and secondary colours. Big cyan, magenta, yellow red, green and blue moments. Martin makes a scroller specifically for the Atomic, and we thought it wouldn't cost too much to hire one for the run. It turns out this wasn't the case - I tried everyone in Sydney who had one and the cheapest I could get was $400 a week - I imagine because they didn't want to hire one without the strobe itself attached. On principle I refused to pay this for a device that wasn't even a light - but that's no reason to let go of a good idea, so I went a little bit DIY. After some trial and error I managed to combine two (much cheaper) par 64 scrollers into a single scroller for the Atomic, with the bonus of being able to operate each separately and achieve split colour strobe effects! That being said we didn't end up using the strobe as much as we envisioned, the parcans ended up providing as with many more looks than we anticipated and so we left the strobe out. Perhaps we had enough lights pointing in the audiences eyes anyhow....

The jungle gym was a fantastic set piece, no matter what lights it was hit with it looked amazing. It also had this great quality of playfulness, every time I went near it I couldn't help but climb all over it. Originally we were intending to build it ourselves but then heard

STC had just used one in their production of

War Of The Roses Part 2. We made some enquiries and they offered to hire it to us for much less than it would cost to build one. It was a little bit like recycling - giving an object a second life. It was nice that it had it's own history and we were making it work for us, rather than it being an object we pluck straight out of our imaginations, build, and then destroy when we are done. In my opinion this kind of recycling should happen more often in the theatre scene. We constantly re-interpret the same texts, why not the same objects and spaces?

The A/V content was a collaboration between Mark and his good buddy

Melvin J. Montalban. Melvin has amazing skills with everything filmic and graphic, and as such put together some incredible clips for the show. My job was to source and realise the actual physical objects - the TVs. In the image above you can see the industrial looking one hanging above the jungle gym. This TV not only had to work but also conceal quite a few kilograms of synthetic rain - which had to fall on Alice midway through the show. Originally I was intending to take the speakers out of the TV and put the rain (acrylic plastic chips) inside the actual chassis. In the end I steered away from this because I thought the TV might overheat with all the extra plastic inside. In the end we put a tray underneath and a hopper on the back. This was filled with plastic before each show and would provide a steady stream of rain for a good 40 seconds This was not only a mindblowing moment - one girl asked 'How come her hair isn't wet?' - but left a sea of plastic all over the floor. My favourite moment is pictured above - where the lights fade up after the rain. The 7 second fade was just perfect, with the TV still swinging on its chains. Like opening the gates to a wasteland. The plastic then went on to pick up the image in the next scene where we projected on the floor. Magic.

Equipment:

24 x Par 64 MFL

8 x Par 64 NSP (used for the 8 cans closest to the floor)

6 x Selecon 1000w Fresnel

1 x Martin Atomic 3000 Strobe

2 x Camelont Rainbow Scroller

1 x Look Solutions Unique 2 Hazer

1 x Jands Event 48

3 x Jands FP12 dimmer rack

1 x Jands GP12 dimmer rack

1 x Panasonic PT-D4000E Projector (rigged to project on floor)

2 x TV

2 x Scan converter

3 x Computer Monitor

1 x Mac G5 Pro with 6 x DVI-I Ouputs. Running Qlab.

A big thanks to Emma Lockheart-Wilson, Amber Silk, Daniel Potter and Alistair Davies .

Photos by Tania Lambert

Project: ALICE is a new Australian work inspired by the Lewis Caroll classic Alice in Wonderland. It rewrites the tale from a generation Y perspective, exploring the rabbit holes of technology and isolation. It premiered in Track 8, CarriageWorks, Sydney, Australia in May 2009.

Project: ALICE is a new Australian work inspired by the Lewis Caroll classic Alice in Wonderland. It rewrites the tale from a generation Y perspective, exploring the rabbit holes of technology and isolation. It premiered in Track 8, CarriageWorks, Sydney, Australia in May 2009.